Ateş fırtınası

Ateş fırtınası veya Alev fırtınası bir yangının felakete dönüşmesini sağlayan ve şiddetlenerek devam etmesini sağlayan bir doğa fenomeni. Ateş fırtınasında sırasında yangın kendi rüzgâr sisetmini oluşturuyor ve bu rüzgârları şiddetlendirerek içine çekiyor. Genelde bu doğa fenomeni doğal yollarla meydana geliyor, özellikle çalı yangınlarından ve orman yangınlarından oluşuyor. Victoria'daki çalı yangınları, Büyük Peshtigo yangını, Victoria ve Güney Avustralya çalı yangınları veya 1906 San Francisco depreminden sonra oluşan yangın, doğal yollarla oluşan alev fırtınalarından birkaç örnek. Ateş fırtınası ayrıca kasıtlı bir şekilde patlayıcı maddeler sonucunda oluşturulabillir, bu yöntemlerden arasında yangın bombardımanı ve alan bombardımanı var. Kasıtlı bir şekilde oluşan alev fırtınaları arasında Hammburg bombardımanı, Dresden bombardımanı, Tokyo bombardımanı ve Hiroşima'ya atom bombası saldırısı sonucu oluşan alev fırtınaları gösterilebillir.

Mekanizm

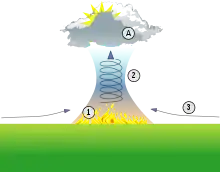

Ateş fırtınası baca etkisi sonucu oluşan bir fenomen. Oluşan alevler, çevredeki havayı içine daha çok çekerek, daha da güçleniyor ve sert rüzgârların esmesini sağlıyor. Bu hava akımı ateşin yakınlarında veya üstünde esen bir jet stream sonucu daha çok güçlenebillir. Ateşin etrafında oluşan sert rüzgârlar, tekrar alevlerin içine esmesi sonucu, ateş fırtınasının daha da güçlenmesini sağlıyabillir.

This would seem to prevent the firestorm from spreading on the wind, but the tremendous turbulence also created causes the strong surface inflow winds to change direction erratically. This wind shear is capable of producing small tornado- or dust devil-like circulations called fire whirls which can also dart around erratically, damage or destroy houses and buildings, and quickly spread the fire to areas outside the central area of the fire. A firestorm may also develop into a mesocyclone and induce true tornadoes.[1] Probably, this is true for the Peshtigo Fire.[2]

The greater draft of a firestorm draws in greater quantities of oxygen, which significantly increases combustion, thereby also substantially increasing the production of heat. The intense heat of a firestorm manifests largely as radiated heat (infrared radiation) which ignites flammable material at a distance ahead of the fire itself. This also serves to expand the area and the intensity of the firestorm. Violent, erratic wind drafts suck movables into the fire, while people and animals caught close or under the fire die for lack of available oxygen. Radiated heat from the fire can melt asphalt, metal, and glass, and turn street tarmac into flammable hot liquid. The very high temperatures replicate the conditions of a smelting furnace, where anything that might possibly burn does so readily, until the firestorm runs out of fuel.

Besides the enormous ash cloud produced by a firestorm, under the right conditions, it can also induce condensation, forming a pyrocumulus cloud or "fire cloud". A large pyrocumulus can grow into a pyrocumulonimbus and produce lightning, which can set off further fires. Apart from forest fires, pyrocumulus clouds can also be produced by volcanic eruptions.

In Australia, the prevalence of eucalyptus trees that have oil in their leaves results in forest fires that are noted for their extremely tall and intense flame front. Hence the bush fires appear more as a firestorm than a simple forest fire. Sometimes, emission of combustible gases from swamps (e.g., methane) has a similar effect. For instance, methane explosions enforced the Peshtigo Fire.[2][3]

In cities

The same underlying combustion physics can also apply to man-made structures such as cities during war or disaster.

Firestorms are thought to have been part of the mechanism of large urban fires such as the Great Fire of Rome, the Great Fire of London, the 1871 Great Chicago Fire, and the fires resulting from the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake. Firestorms were also created by the firebombing raids of World War II in cities like Hamburg, and Dresden.[4]

| City / Event | Date of the firestorm | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bombing of Hamburg (Germany)[4] | 27 July 1943 | 46,000 dead.[5] |

| Bombing of Dresden (Germany)[4] | 13 February 1945 | maximum of 25,000 dead.[6] |

| Firebombing of Tokyo (Japan) | 9-10 March 1945 | Firestorm covering 16 milkare (41 km2). 267,171 buildings destroyed, 83,793 dead.[7] The most devastating air raid in history with destruction greater than the Atomic bombing of Hiroshima, although with fewer casualties.[7] |

| Atomic bombing of Hiroshima (Japan) | 6 August 1945 | Firestorm covering 4,4 milkare (11 km2).[8] The proportion of firestorm victims who survived the initial blast can never be known. |

Firebombing

Firebombing is a technique designed to damage a target, generally an urban area, through the use of fire, caused by incendiary devices, rather than from the blast effect of large bombs. Such raids often employ both incendiary devices and high explosives. The high explosive destroys roofs making it easier for the incendiary devices to penetrate the structures and cause fires and the high explosives disrupt the ability of firefighters to douse the fires.[4]

Although simple incendiary bombs have been used to destroy buildings since the start of gunpowder warfare, World War II saw the first use of strategic bombing from the air to destroy the ability of the enemy to wage war. London, Coventry and many other British cities were firebombed during the Blitz. Most large German cities were extensively firebombed starting in 1942 and almost all large Japanese cities were firebombed during the last six months of World War II. However as Sir Arthur Harris, the officer commanding RAF Bomber Command from 1942 through to the end of the war in Europe, pointed in his post war analysis, although many attempts were made to create deliberate man made firestorms during World War II few attempts succeed:

| « The Germans again and again missed their chance, ... of setting our cities ablaze by a concentrated attack. Coventry was adequately concentrated in point of space, but all the same there was little concentration in point of time, and nothing like the fire tornadoes of Hamburg or Dresden ever occurred in this country. But they did do us enough damage to teach us the principle of concentration, the principle of starting so many fires at the same time that no fire fighting services, however efficiently and quickly they were reinforced by the fire brigades of other towns could get them under control. » | |

(Arthur Harris) |

Ayrıca bakınız

Notes

- Weaver & Biko.

- Gess & Lutz 2003, s.

- Kartman & Brown 1971, s. 48.

- Harris 2005, s. 83

- Frankland & Webster 1961, ss. 260-261.

- Neutzner 2010, s. 70.

- Michael D. Gordin (2007). Five days in August: how World War II became a nuclear war. Princeton University Press. s. 21. ISBN 0-691-12818-9.

- McRaney & McGahan 1980, s. 24.

Kaynakça

- Gess, Denise; Lutz, William (2003) [2002], Firestorm at Peshtigo: A Town, Its People, and the Deadliest Fire in American History, ISBN 978-0-8050-7293-8

- Frankland, Noble; Webster, Charles (1961), The Strategic Air Offensive Against Germany, 1939-1945, Volume II: Endeavour, Part 4, Londra: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, ss. 260-261

- Harris, Arthur (2005), Bomber Offensive (First, Collins 1947 bas.), Pen & Sword military classics, s. 83, ISBN 1-84415-210-3

- Kartman, Ben; Brown, Leonard (1971), Disaster!, Essay Index Reprint Series, Ayer Publishing, s. 48, ISBN 978-0-8369-2280-6

- McRaney, W.; McGahan, J. (6 Ağustos 1980), Radiation dos reconstruction U.S. occupation forces in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, 1945–1946 (DNA 5512F) — Final Report for Period 7 March 1980-6 August 1980 (PDF), Science Applications, Inc, s. 24, 24 Haziran 2006 tarihinde kaynağından (PDF) arşivlendi, erişim tarihi: 5 Nisan 2012

- Neutzner, Matthias (2010), Abschlussbericht der Historikerkommission zu den Luftangriffen auf Dresden zwischen dem 13. und 15. Februar 1945 (PDF), Landeshauptstadt Dresden, s. 70, 21 Mayıs 2012 tarihinde kaynağından (PDF) arşivlendi, erişim tarihi: 7 Haziran 2011

- Pyne, Stephen J. (2001), Year of the Fires: The Story of the Great Fires of 1910, Viking-Penguin Press, ISBN 0-670-89990-9

- Weaver, John; Biko, Dan, Firestone Induced Tornado, erişim tarihi: 12 Ocak 2020