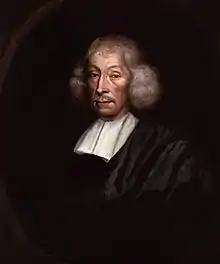

John Ray

John Ray (d. 29 Kasım 1627 - ö. 17 Ocak 1705), İngiliz doğabilimci ve bitki bilimci. Bitki bilim mahlası Ray'dir.[1]

John Ray | |

|---|---|

| |

| Doğum |

29 Kasım 1627 Black Notley |

| Ölüm |

17 Ocak 1705 (77 yaşında) Black Notley |

| Milliyet | İngiliz |

| Meslek | Botanist, Zoolojist |

1670 yılına kadar John Wray olarak yazmış, bu tarihten itibaren ise Ray soy adını tercih etmiştir. Botanik, zooloji ve doğal teoloji üzerine eserler kaleme almıştır. Historia Plantarum adlı eserindeki sınıflandırması, bitkilerin modern taksonomik sınıflandırması için önemli bir adım olarak kabul edilir. Biyolojide tür kavramını ilk tanımlayan kişiler arasındadır.[2]

Hayatı

Essex'e bağlı Black Notley'da doğdu. O'na göre babası demirci idi ve kendisi de demirhanede doğmuştu. Trinity College'da eğitim görürken on altı yaşında iken Cambridge Üniversitesi'ne gönderildi.

1673 yılında Margaret Oakley ile evlendi. 1679 yılında ise doğduğu Black Notley'a taşındı. Sağlığının bozulmasına ve çok sayıda kronik rahatsızlığı olmasına rağmen buradaki hayatı sükunet içinde geçti. Burada arkadaşı Samuel Dale ile bilimsel içerikli mektuplaşmalarını sürdürdü.[3]

77 yaşında iken Black Notley'da hayatını kaybetti ve adına yapılan bir anıtın da bulunduğu St Peter ve St Paul kilisesinin bahçesine gömüldü. İngiliz rahip doğa bilimcilerinin öncülerinden olarak kabul edilir.[4]

Sınıflandırma sistemi

Herbae divizyonu;

- Bulbosae (Lilium vs.)

- Tuberosae (Asphodelus vs.)

- Umbelliferae (Foeniculum vs.)

- Verticellatae (Mentha vs.)

- Spicatae (Lysimachia vs.)

- Scandentes (Cucurbita vs.)

- Corymbiferae (Tanacetum)

- Pappiflorae (Senecio vs.)

- Capitatae (Scabiosa vs.)

- Campaniformes (Digitalis vs.)

- Coronariae (Dianthus vs.)

- Rotundifoliae (Cyclamen vs.)

- Nervifoliae (Plantago vs.)

- Stellatae (Rubia vs.)

- Cerealia (Leguminosae vs.)

- Succulentae (Sedum vs.)

- Graminifoliae (Gramineae vs.)

- Oleraceae (Beta etc.)

- Aquaticae (Nymphaea etc.)

- Marinae (Fucus etc.)

- Saxatiles (Asplenium etc)[5]

Historia Plantarum (1685–1703) adlı eserinde:[6]

- Herbae (Otsu bitkiler)

- Imperfectae (Kriptogamlar)

- Perfectae (Tohumlu bitkiler)

- Arborae (Ağaçlar)

- Monocotyledons

- Dicotyledons

Önemli eserleri

- Ray, John (1660). Catalogus plantarum circa Cantabrigiam nascentium ...: Adiiciuntur in gratiam tyronum, index Anglico-latinus, index locorum ... [Catalogue of Cambridge plants] (Latince). Cambridge: John Field. 4 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020. Appendices 1663, 1685

- Ray, John (1975). Catalogus Plantarum Circa Cantabrigiam Nascentium [Ray's Flora of Cambridgeshire]. trans. Ewen & Prime. Wheldon and Wesley. ISBN 978-0-85486-090-6. 4 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- Ray, John (2011). John Ray's Cambridge Catalogue (1660). trans. Oswald and Preston. Ray Society. ISBN 978-0-903874-43-4. 4 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- 1668: Tables of plants, in John Wilkins' Essay

- Ray, John (1677) [1668]. Catalogus plantarum Angliae, et insularum adjacentium: tum indigenas, tum in agris passim cultas complectens. In quo praeter synonyma necessaria, facultates quoque summatim traduntur, unà cum observationibus & experimentis novis medicis & physics [Catalogue of English plants] (latin) (2nd bas.). Londra: A Clark. 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- 1670: Collection of English proverbs.

- 1673: Observations in the Low Countries and Catalogue of plants not native to England.

- 1674: Collection of English words not generally used.online 2 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.

- 1675: Trilingual dictionary, or nomenclator classicus.

- 1676: Willughby's Ornithologia 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi..[lower-alpha 1]

- Ray, John (1682). Methodus plantarum nova: brevitatis & perspicuitatis causa synoptice in tabulis exhibita, cum notis generum tum summorum tum subalternorum characteristicis, observationibus nonnullis de seminibus plantarum & indice copioso [New method of plants] (latin). Londra: Faithorne & Kersey. 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- 1686: History of fishes.[lower-alpha 2]

- 1686–1704: Historia plantarum species [History of plants]. London:Clark 3 vols;

- Vol 1 1686 4 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi., Vol 2 1688 4 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi., Vol 3 1704 3 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi. (in Latin)[lower-alpha 3]

- Lazenby, Elizabeth Mary (1995). The Historia Plantarum Generalis of John Ray, Book I : a translation and commentary. PhD thesis Newcastle University 2 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.

- Ray, John (1690). Synopsis methodica stirpium Britannicarum: in qua tum notae generum characteristicae traduntur, tum species singulae breviter describuntur: ducentae quinquaginta plus minus novae species partim suis locis inseruntur, partim in appendice seorsim exhibentur : cum indice & virium epitome [Synopsis of British plants] (Latin). Londra: Sam. Smith. 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- 2nd ed 1696

- 1691: The wisdom of God Manifested in the Works of the Creation 7th ed.7 Ağustos 2015 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi. 2nd ed 1692, 3rd ed 1701, 4th ed 1704, 7th ed 1717{{efn|7th ed. Printed by R. Harbin, for William Innys, at the Prince’s-Arms in St Paul’s Church Yard, London 1717. Each edition enlarged from the previous edition. This was his most popular work. It was in the vein later called natural theology, explaining the adaptation of living creatures as the work of God. It was heavily plagiarised by William Paley in his Natural theology of 1802.[7]

- 1692: Miscellaneous discourses concerning the dissolution and changes of the world 4 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.[lower-alpha 4]

- 1693: Synopsis of animals and reptiles 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi..

- 1693: Collection of travels.

- 1694: Collection of European plants.

- 1695: Plants of each county. (Camden's Britannia)

- Ray, John (1696). De Variis Plantarum Methodis Dissertatio Brevis [Brief dissertation] (latin). Londra: Smith & Walford.

- 1700: A persuasive to a holy life.

- Ray, John (1703). Methodus plantarum emendata et aucta: In quãa notae maxime characteristicae exhibentur, quibus stirpium genera tum summa, tum infima cognoscuntur & áa se mutuo dignoscuntur, non necessariis omissis. Accedit methodus graminum, juncorum et cyperorum specialis (latin). Londra: Smith & Walford. 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- Ölümünden sonra yayımlananlar

- 1705. Method and history of insects

- 1713: Synopsis methodica avium & piscium: opus posthumum (Synopsis of birds and fishes), in Latin. William Innys, London 20 Mart 2017 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi. vol. 1: Avium vol. 2: Piscium

- 1713 Three Physico-theological discourses 2 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.[lower-alpha 5]

- Ray, John (1724) [1690]. Dillenius, Johann Jacob (Ed.). Synopsis methodica stirpium Britannicarum: in qua tum notae generum characteristicae traduntur, tum species singulae breviter describuntur: ducentae quinquaginta plus minus novae species partim suis locis inseruntur, partim in appendice seorsim exhibentur: cum indice & virium epitome (editio tertia multis locis emendata, & quadringentis quinquaginta circiter speciebus noviter detectis aucta ) [Synopsis of British plants] (Latin) (3rd bas.). Londra: Gulielmi & Joaniis Innys. 5 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020. Kaynak kaldırılmış

|editorlink=parametresini kullanıyor (yardım)- Facsimile edition 1973, Ray Society, London. With introduction by William T. Stearn. 978-0-903874-00-7

- Fourth edition 1760

Mirası

1844 yılında kurulan Ray Society adını O'ndan almaktadır.[12]

| Vikisöz'de John Ray ile ilgili sözleri bulabilirsiniz. |

Kaynakça

- "IPNI". 8 Eylül 2019 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 16 Ağustos 2020.

- Historia plantarum generalis, in the volume published in 1686, Tome I, Libr. I, Chap. XX, page 40 (Quoted in Mayr, Ernst. 1982. The growth of biological thought: diversity, evolution, and inheritance. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press: 256)

- Morris, A. D. (1974). Samuel Dale (1659-1739), Physician and Geologist. Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine, 67, 120–124. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/003591577406700215 2 Ağustos 2020 tarihinde Wayback Machine sitesinde arşivlendi.

- Armstrong 2000, pp. 45ff.

- Slaughter 1982, pp. 62–63.

- Singh 2004, John Ray p. 302.

- Keynes, Sir Geoffrey [1951] 1976. John Ray, 1627–1705: a bibliography 1660–1970. Van Heusden, Amsterdam.

- Newton, Alfred 1893. Dictionary of birds. Black, London

- Raven 1950.

- Bowler, Peter J. (2003). Evolution: the history of an idea (3rd bas.). California.

- Hooke, Robert 1705. The posthumous works of Robert Hooke. London. repr. 1969 Johnson N.Y.

- "The Ray Society". 13 Ocak 2012 tarihinde kaynağından arşivlendi. Erişim tarihi: 25 Aralık 2017.

- "In fact, the book was Ray's, based on preliminary notes by Francis Willughby".[7] "Willughby and Ray laid the foundation of scientific ornithology".[8]

- Plates subscribed by Fellows of the Royal Society. Samuel Pepys, the President, subscribed for 79 of the plates.

- The third volume lacked plates, so his assistant James Petiver published Petiver's Catalogue in parts, 1715–1764, with plates. The work on the first two volumes was supported by subscriptions from the President and Fellows of the Royal Society

- This includes some important discussion of fossils. Ray insisted that fossils had once been alive, in opposition to his friends Martin Lister and Edward Llwyd. "These [fossils] were originally the shells and bones of living fishes and other animals bred in the sea". Raven commented that this was "The fullest and most enlightened treatment by an Englishman" of that time.[9]p426

- This is the 3rd edition of Miscellaneous discourses, the last by Ray before his death, and delayed in publication. Its main importance is that Ray recanted his former acceptance of fossils, apparently because he was theologically troubled by the implications of extinction.[10]p37 Robert Hooke, like Nicolas Steno, was in no doubt about the biological origin of fossils. Hooke made the point that some fossils were no longer living, for example Ammonites: this was the source of Ray's concern.[11]p327